Chapter 3: Lebanon

Lebanon

Burj Al-Barajneh

Jal Al-Bahr

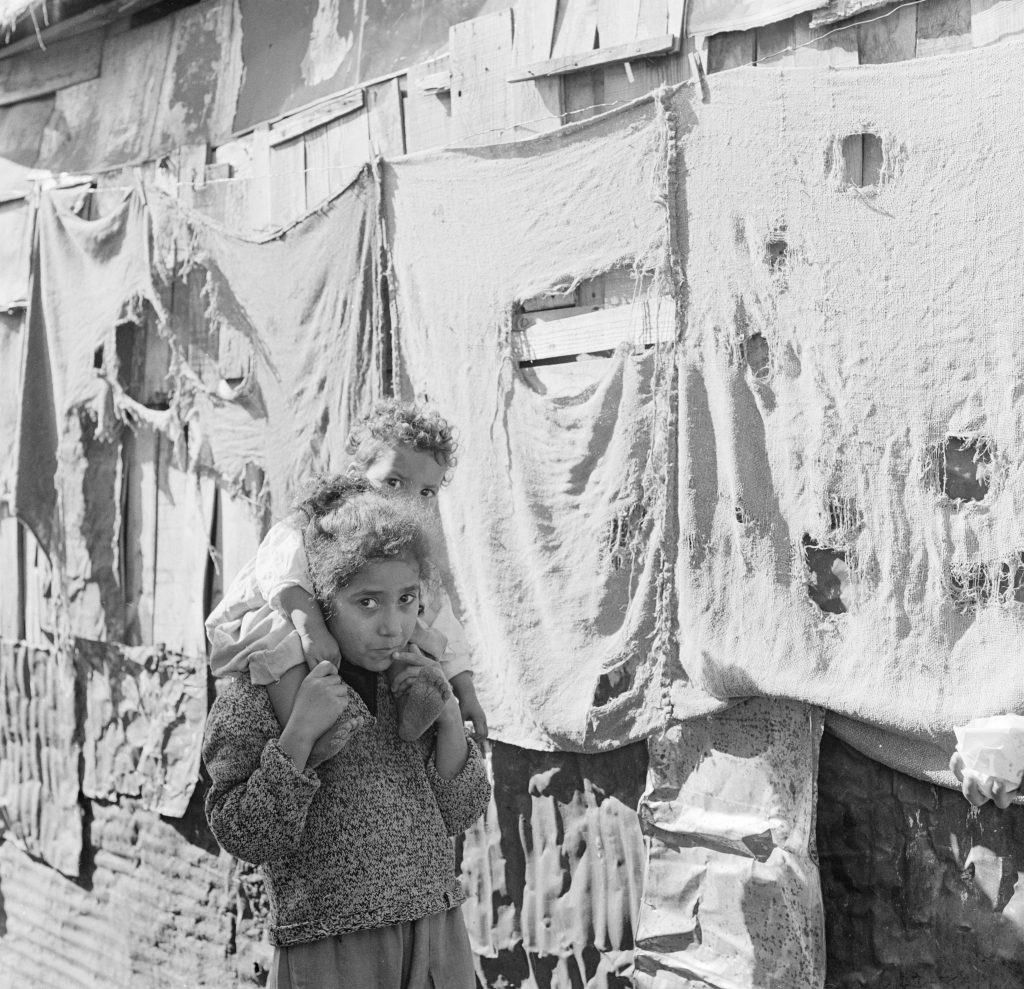

During the 1948 Arab-Israeli war hundreds of thousands of Palestinians fled or were expelled and displaced from their homes in what is now Israel. A large group of them sought refuge in neighboring Lebanon. Seven decades on, Palestinian refugees and their descendants, who are also considered refugees, still live in official and informal camps across the five governorates of the country. An official census conducted in 2017 recorded the number of Palestinian refugees resident in Lebanon as 174,422 individuals, living in 12 official camps and 156 informal camps. A much higher number of Palestinian refugees – some 450,000 – are registered in Lebanon with the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA), which runs the official camps, but the agency acknowledges that many of them live outside the country.

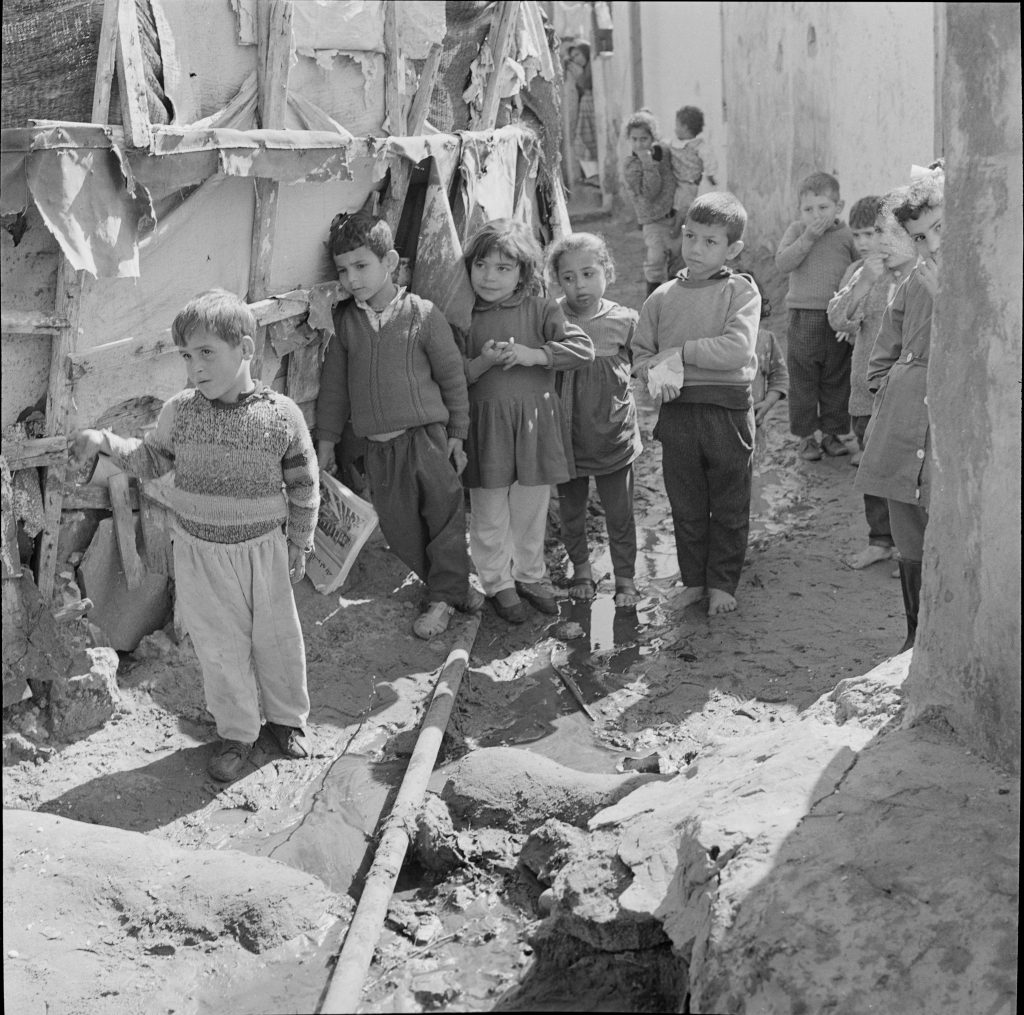

The amount of land allocated to official camps has barely changed over the years. Palestinian refugees have therefore been forced to expand the buildings in the camps upwards, which can lead to people living in unsafe structures. Conditions in the camps are overcrowded. Infrastructure and services such as sewage and electricity have been further strained since Palestinian refugees from Syria have been forced to flee the conflict and sought safety in Palestinian camps in Lebanon. By December 2016, there were 32,000 Palestinian refugees from Syria registered with UNRWA in Lebanon – with almost 90% of them living below the poverty line and 95% of them described as “food insecure”.

The Lebanese authorities impose severe restrictions on Palestinian refugees’ access to public services, such as medical treatment and education, as well as on their access to the Lebanese labour market, thereby contributing to high levels of unemployment, low wages and poor working conditions for this population. Successive Lebanese governments have claimed that removing such restrictions would lead to the assimilation of Palestinian refugees into Lebanese society and therefore impede their right to return.

Until 2005, Palestinian refugees in Lebanon were effectively barred from the formal job market and therefore forced to work in informal, generally low-paid, employment.

In June 2005, the Minister of Labour issued a memorandum allowing Palestinians born on Lebanese soil and officially registered with the Ministry of Interior and UNRWA to obtain work permits. The development followed a “right to work” campaign organized by the NGO Association Najdeh along with 45 other Lebanese civil society and Palestinian refugee grassroots organizations with the aim of lifting the discriminatory measures against Palestinian refugees. This gave Palestinian refugees access to 70 occupations that had previously been prohibited to them, although the cost of the work permits and the bureaucratic procedures required to obtain them continued to present significant obstacles. The continued application of this measure is subject to the discretion of each individual minister of labour.

In August 2010, the Lebanese parliament passed further amendments to labour and social security laws to facilitate Palestinian refugees’ access to work, including waiving the fees for work permits.

However, Palestinian refugees are still prohibited from practising over 30 professions in the fields of public service, health care, engineering, law, transport and fishing, among others. Access to these professions is controlled by syndicates. Some syndicates restrict membership and thus the practice of the profession to Lebanese citizens. Others, such as those of doctors, pharmacists and engineers, impose a condition of reciprocity of treatment, meaning that foreign nationals can only access the profession if Lebanese nationals have the right to practise that profession in their country. This condition remains impossible to meet in light of the current international status of the State of Palestine.

Even in occupations where Palestinian refugees are now entitled to work, they still face discrimination compared to Lebanese co-workers. While everyone is obliged to pay 23.5% of their salary to the National Social Security Fund, Palestinian refugees only benefit from it by gaining access to an end-of-service indemnity (equivalent to 8.5% of the value of the payments they have made). Unlike their Lebanese counterparts, they do not receive public health insurance as a consequence of their contributions. The cost of private health insurance falls on either the Palestinian refugee or their employer, who may be discouraged from hiring such an employee as a result. Many Palestinian refugees continue to work in the informal sector, where they are generally forced to accept harsh working conditions, low wages and no legal protection.

Amnesty International calls on Lebanon to recognize Palestinian refugees as refugees and guarantee their rights to work, health, education and housing. These refugees are unable to move to Israel or the Occupied Palestinian Territories given the Israeli authorities’ refusal to comply with UN General Assembly Resolution 194 protecting the right to return of Palestinian refugees, including those residing currently in Lebanon.

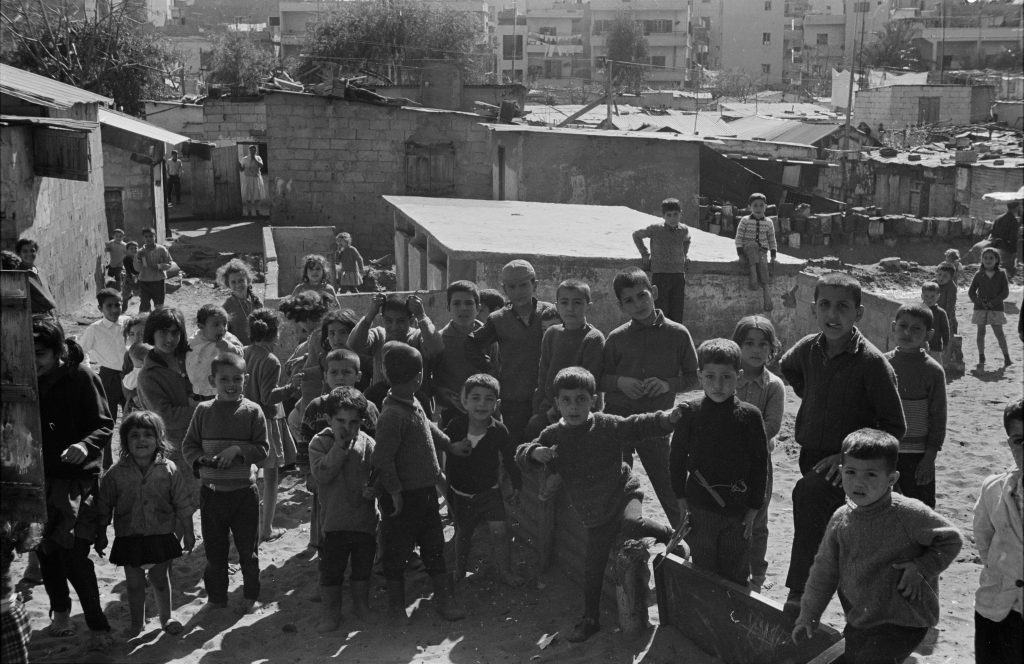

The League of Red Cross Societies established the Burj Al-Barajneh camp in the southern suburbs of Beirut in 1948 to accommodate refugees who had fled from Galilee in northern Palestine. According to UNRWA, it is the most densely populated camp in Beirut and suffers from problems of overcrowding and inadequate basic infrastructure. Several years of restrictions imposed by the Lebanese authorities mean that many residents live in makeshift or crumbling structures with virtually no private space. Residents of Burj Al-Barajneh suffered immensely during the Lebanese civil war. The camp was almost entirely destroyed in the mid-1980s as a result of indiscriminate shelling, which also led to the displacement of nearly a quarter of the camp’s population.

According to the NGO Beit Atfal Assumoud, which has been active in the camp since 1985, the camp, which is around 1km2 in area, has around 40,000 residents, including some 28,000 Palestinian refugees from Lebanon, some 4,000 Palestinian refugees from Syria and some 8,000 people of other nationalities. Many of the men in the camp work as day labourers in construction and women there are employed mainly in sewing factories or as domestic workers.

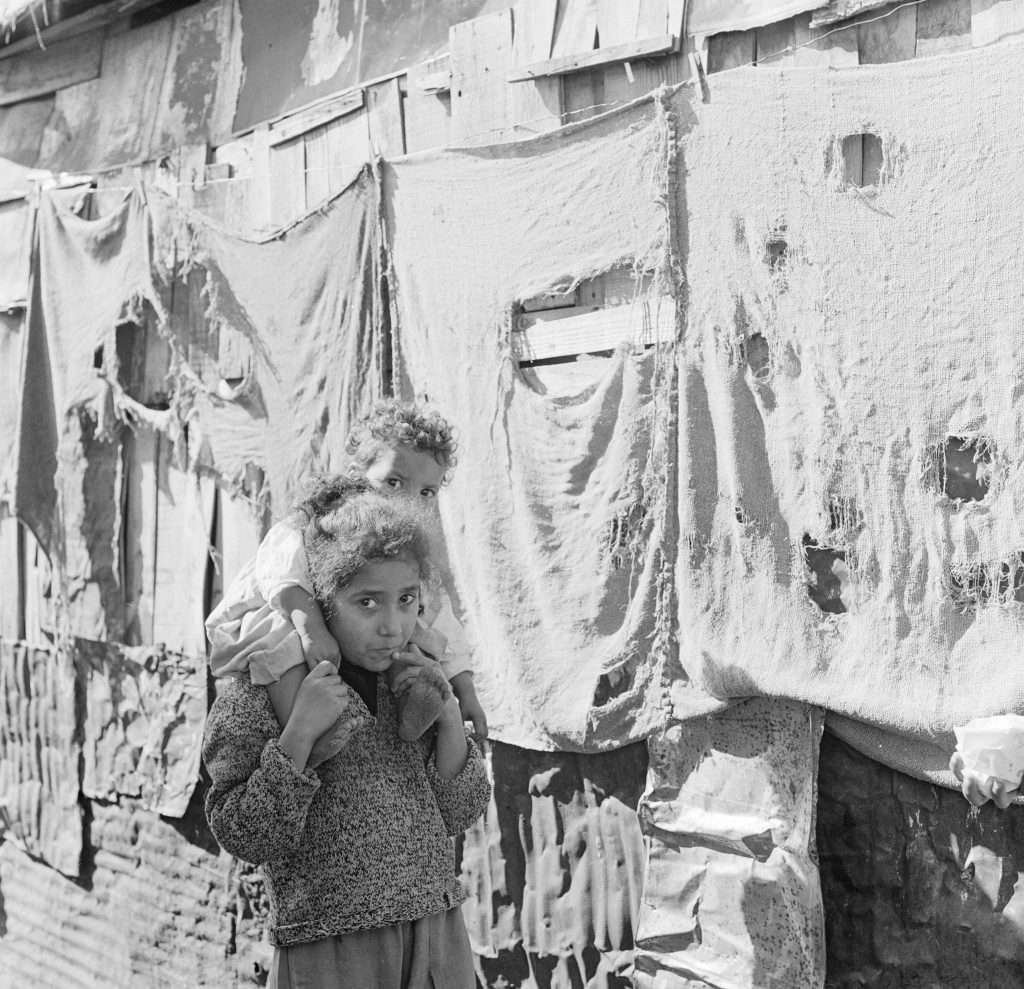

Jal Al-Bahr is an informal camp located on the coast at the northern entrance to the city of Tyr in southern Lebanon. Due to its unofficial status, there is no accurate data available on the population in Jal Al-Bahr. However, according to camp residents, the population stands at around 2,500 persons living in 240 housing units, the majority of them makeshift structures built out of zinc sheets. UNRWA does not manage the camp and therefore does not provide health or educational services there. Instead, refugees living in Jal Al-Bahr have to travel to the nearby El-Buss refugee camp, which is administered by UNRWA, in order to access these essential services. The very location of Jal Al-Bahr is a safety hazard for its inhabitants. In winter, the sea often floods homes in the camp. Fast-moving vehicles on the highway on the other side of the camp present a daily risk to residents who have to cross it to travel elsewhere, such as children whose families cannot afford the cost of transportation by bus to the UNRWA schools in El-Buss.

A socio-economic survey conducted in 2010 by the American University of Beirut, in collaboration with UNRWA, identified the largest concentration of extremely poor Palestinian refugees in Lebanon as living in the informal camps of Jal Al-Bahr and Qasmiyyeh in the south of the country. The majority of Jal Al-Bahr residents work in the fishing industry while others are day labourers in agriculture and construction. Unable to purchase proper fishing boats, Palestinian refugees in Jal Al-Bahr are forced to use makeshift floats made of rubber wheels to fish. The two needs residents of Jal Al-Bahr most frequently highlighted to Amnesty International were the to strengthen the foundations of their homes to protect them from the sea and to ensure children’s safe access to school.