Chapter 2: Jordan

Jordan

Jerash Camp

Jordan is the country that hosts the largest number of Palestinian refugees (PR). Most but not all of them hold Jordanian nationality.

According to the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA), more than 2 million registered Palestinian refugees now live in Jordan. Most reside in cities and villages alongside Jordanians, while 370,000 live in camps, 10 of them official and three of them unofficial.

Around three quarters of the over 2 million Palestinian refugees in Jordan hold full Jordanian citizenship and therefore have a national identification number, which allows them access to the labour market and public health and education services. However, a significant minority, most of whom arrived in Jordan from the Gaza Strip, as opposed to the West Bank, do not possess Jordanian citizenship. A national census carried out by Jordan’s Department of Statistics in 2016 put their number at 634,182. They are excluded from rights and services enjoyed by citizens and are amongst the most destitute communities in Jordan.

The difference in treatment between Palestinian refugees who moved to Jordan from Gaza and those who came from the West Bank has its roots in the history of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

Following the 10-month Arab-Israeli war in 1948, the Egyptian army took control of the Gaza Strip, while Jordan’s Arab Legion entered the West Bank, including East Jerusalem.

Jordan formally annexed the West Bank on 24 April 1950 in a move that gained little recognition from the international community. It was a source of considerable disagreement within the Arab League, which ended up adopting what was considered then a face-saving solution: “to treat the Arab part of Palestine annexed by Jordan as a trust in its hands until the Palestine case is fully solved in the interests of its inhabitants”.

To further formalize the status of the newly added population and territory, Jordan, under the rule of King Hussein bin Talal, issued a nationality law in 1954 extending Jordanian citizenship to “any person who, not being Jewish, possessed Palestinian nationality before 15 May 1948 and was a regular resident in [Jordan] between 20 December 1949 and 16 February 1954”. This measure covered all residents in the West Bank, including refugees who had been displaced from other Palestinian villages and cities in what is now Israel. Meanwhile, Gaza and its residents remained under Egyptian control.

The annexation more than doubled the population of Jordan and the new citizens were granted equal access to work in all sectors of the state and half the seats of the Jordanian parliament were reserved for representatives they elected. The developments did not, however, lead automatically to changes in the economic situation of Palestinian refugees and many continued to live in camps, where they received UNRWA assistance for health care and education.

The annexation persisted until the defeat of the Arab armies in the June 1967 war with Israel. As a result of the war, the West Bank, including East Jerusalem, and the Gaza Strip came under Israeli military occupation. Around 300,000 Palestinian refugees fled both the West Bank and Gaza to Jordan during and in the aftermath of the conflict.

After the war, the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO), under the chairmanship of Yasser Arafat, moved its base to Jordan, from where it launched military operations against Israel. As the PLO’s power grew, its leadership began criticizing what they characterized as King Hussein’s conciliatory policies towards Israel and challenged his claims to the West Bank, as well as his control of Jordan. Some factions within the PLO ended up calling for Jordan’s monarchy to be overthrown. In response, Jordan launched a military campaign against the PLO and, by July 1971, had forced it out of Jordan. The campaign was dubbed “Black September” and resulted in the relocation of the PLO to Lebanon.

In July 1988, at the height of the first Palestinian Intifada (uprising) against Israeli military occupation and amidst growing support for the PLO, Jordan relinquished its claims to the West Bank. King Hussein announced the severance of all administrative and legal ties with the occupied West Bank and explained his decision as one of deference to Palestinian wishes for national autonomy.

Jordan’s borders were thus reset to pre-1948 boundaries and its population no longer included all those living in the West Bank. Jordan kept guardianship over Muslim and Christian holy sites in Jerusalem and joined the Arab League in recognizing the PLO as “the sole legitimate representative of the Palestinian people”.

The decision had a major impact on the 760,000 Palestinians living in the West Bank, who made up 20% of the Jordanian population at the time. Jordan revoked their citizenship and offered them temporary travel documents instead.

Palestinians of West Bank origin who were living in Jordan proper or residing in a third country generally maintained their Jordanian nationality. However, in the 2000s, Jordan arbitrarily cancelled the national identity documents of thousands of these individuals. It revoked their Jordanian citizenship and gave them temporary travel documents that needed to be renewed after a certain period of time, usually ranging from two to five years. These temporary travel documents are not coupled with a national identification number, meaning their holders do not have access to the benefits of Jordanian citizenship.

Palestinian refugees who came to Jordan from the Gaza Strip, many of whom had previously been forcibly displaced from their homes in what became Israel, were never given Jordanian citizenship and have consequently remained stateless. They had had access to Egyptian travel documents during the period of Egypt’s control over the Gaza Strip between 1948 and 1967, but not Egyptian citizenship. When thousands of them escaped Gaza to Jordan after the 1967 war, the Jordanian authorities issued them temporary travel documents, which they and their offspring are still required to renew every two years in a bureaucratic procedure that involves the Ministry of Interior and the approval of the prime minister. Most of these Palestinian refugees reside in refugee camps in Jordan.

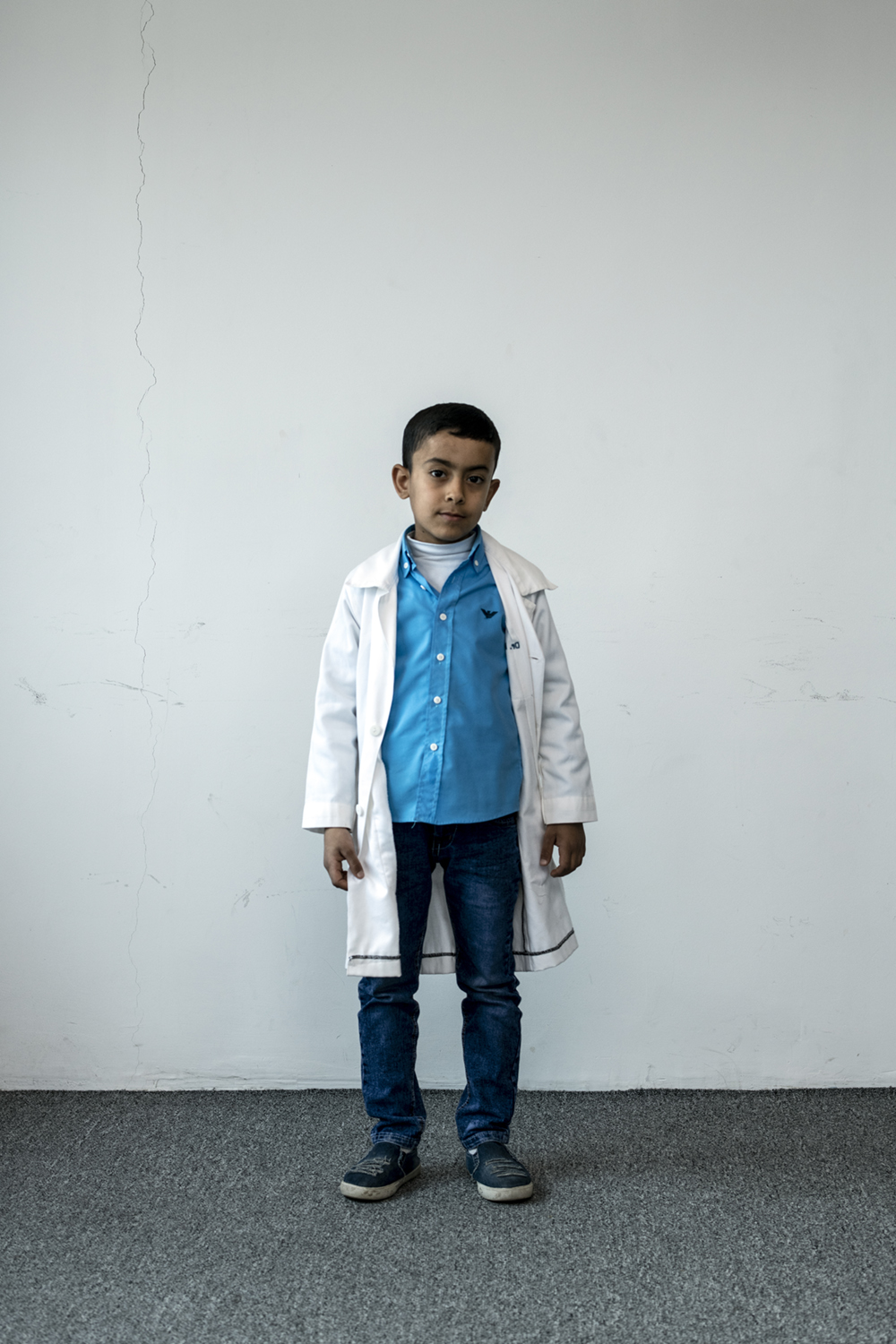

While the temporary travel documents Palestinian refugees without citizenship are issued serve as identity cards, their lack of citizenship places them in an insecure position in Jordan. They lack access to welfare support for the poor. They only benefit from UNRWA’s education and health care services. While they can access public schools and universities, they have to do so as foreigners and thus pay double the tuition fees. They are not eligible for public health insurance, which allows Jordanian citizens access to free or low-cost medical consultations, medicine and hospitalization.

They are barred from most positions of employment in the public sector and need special work permits to obtain jobs in the private sector. They have no access to professions such as law and engineering as jobs in these areas require membership of the relevant syndicate, which is only open to citizens. The Jordanian labour law sets clear restrictions on the work of non-citizens. Article 12 requires the employment of non-Jordanians to be approved by the minister of labour or their delegate. In practice, this means they are expected to either possess a set of skills not found in the Jordanian workforce or work in a sector lacking sufficient Jordanian employees.

Until recently they were unable to own land, property or diesel-run vehicles, whose use is predominantly in commerce and agriculture. On 3 December 2018, following a call from members of the lower house of the Jordanian parliament to alleviate the dire conditions of more than 150,000 Palestinian refugees from Gaza, the government of Prime Minister Omar Al-Razzaz decided to allow heads of families from this group to own property and land of an area not exceeding 1 acre for the purpose of constructing a family house and diesel-run vehicles.

In 2017, among other severe economic measures, the government raised the cost of issuing and renewing temporary travel documents from 25 to 200 Jordanian dinars (from US$35 to 282). To mitigate that hike, the government reconfirmed a 2016 decision to exempt residents who hold temporary travel documents from paying fees for work permits.

Amnesty International calls on Jordan to amend the legal status of Palestinian refugees who are not Jordanian citizens, including those who arrived in the Gaza Strip and their descendants, to ensure their human rights are better protected. These refugees are unable to move to Israel or the Occupied Palestinian Territories given the Israeli authorities’ refusal to comply with UN General Assembly Resolution 194 protecting the right to return of Palestinian refugees, including those residing currently in Jordan.

Whether through naturalization or other measures, the Jordanian authorities should guarantee the rights of these refugees to work, health, education and housing on a par with Jordanian citizens.

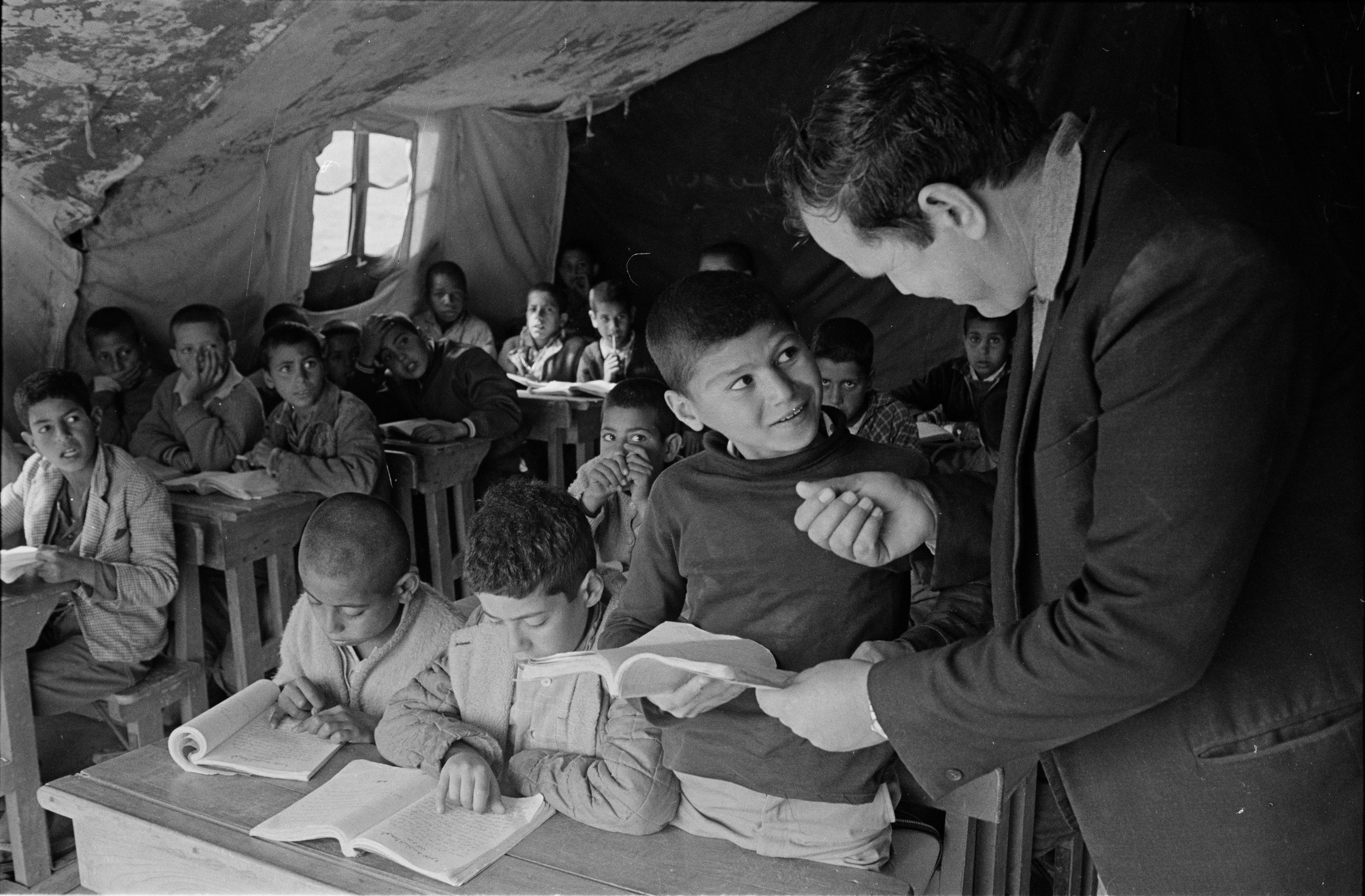

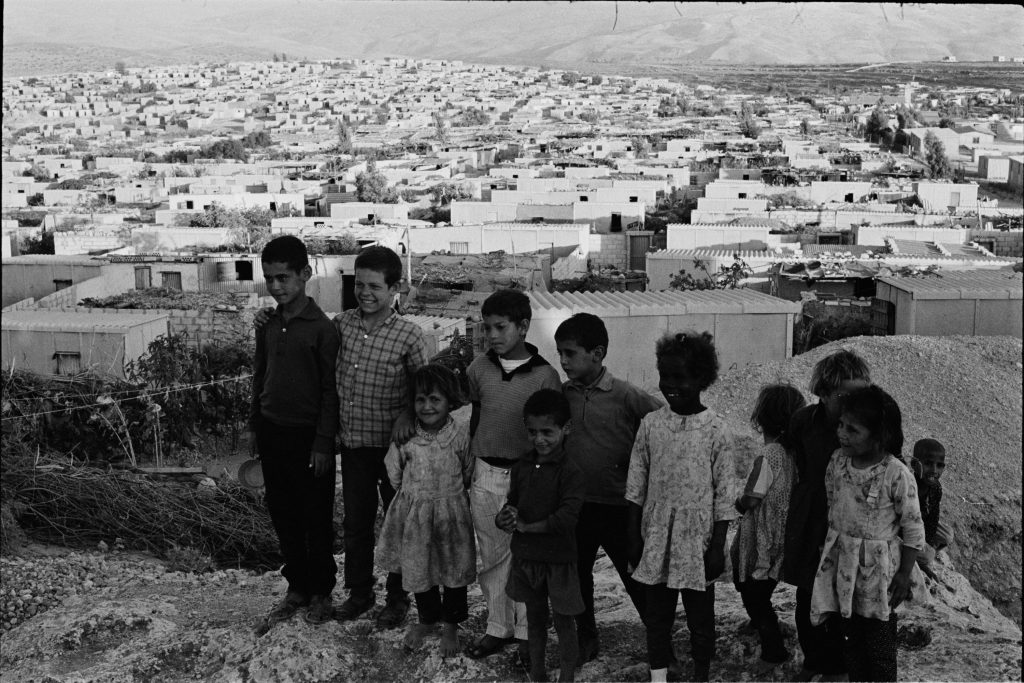

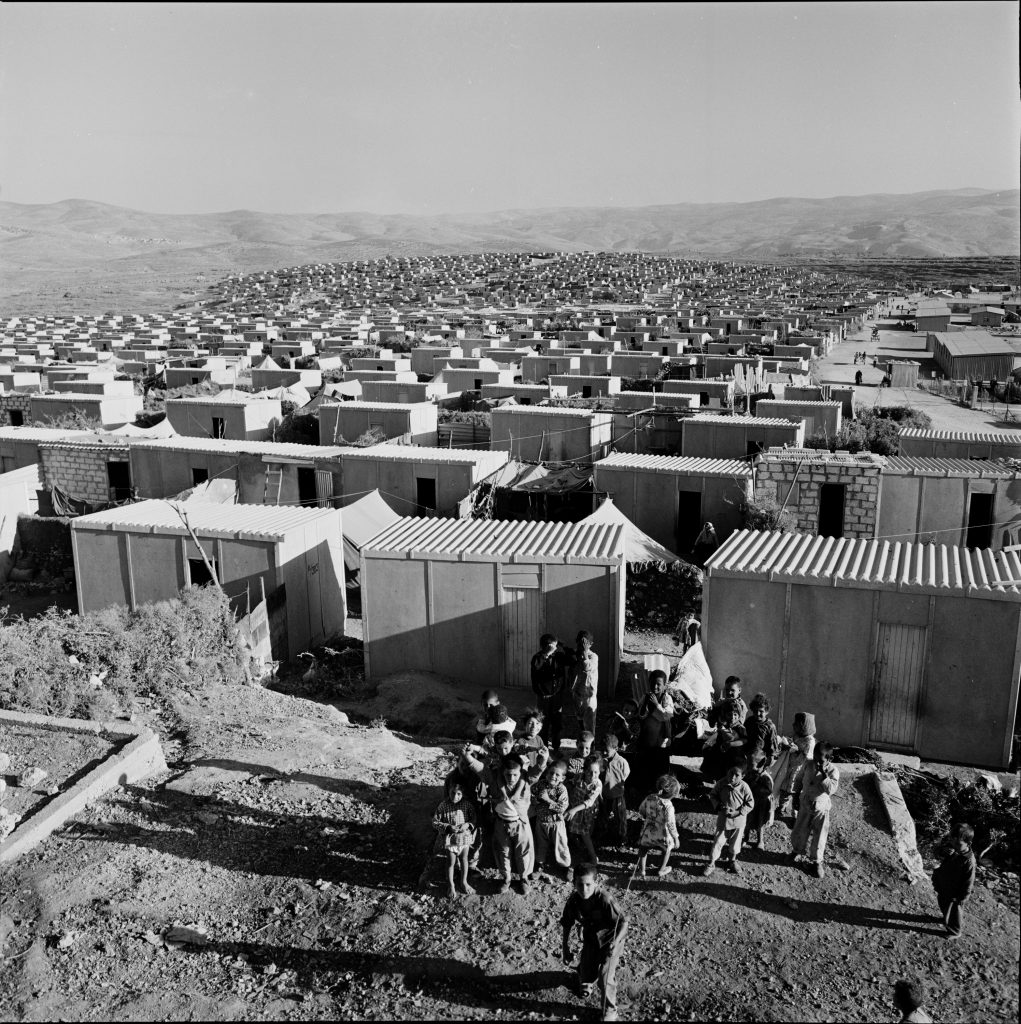

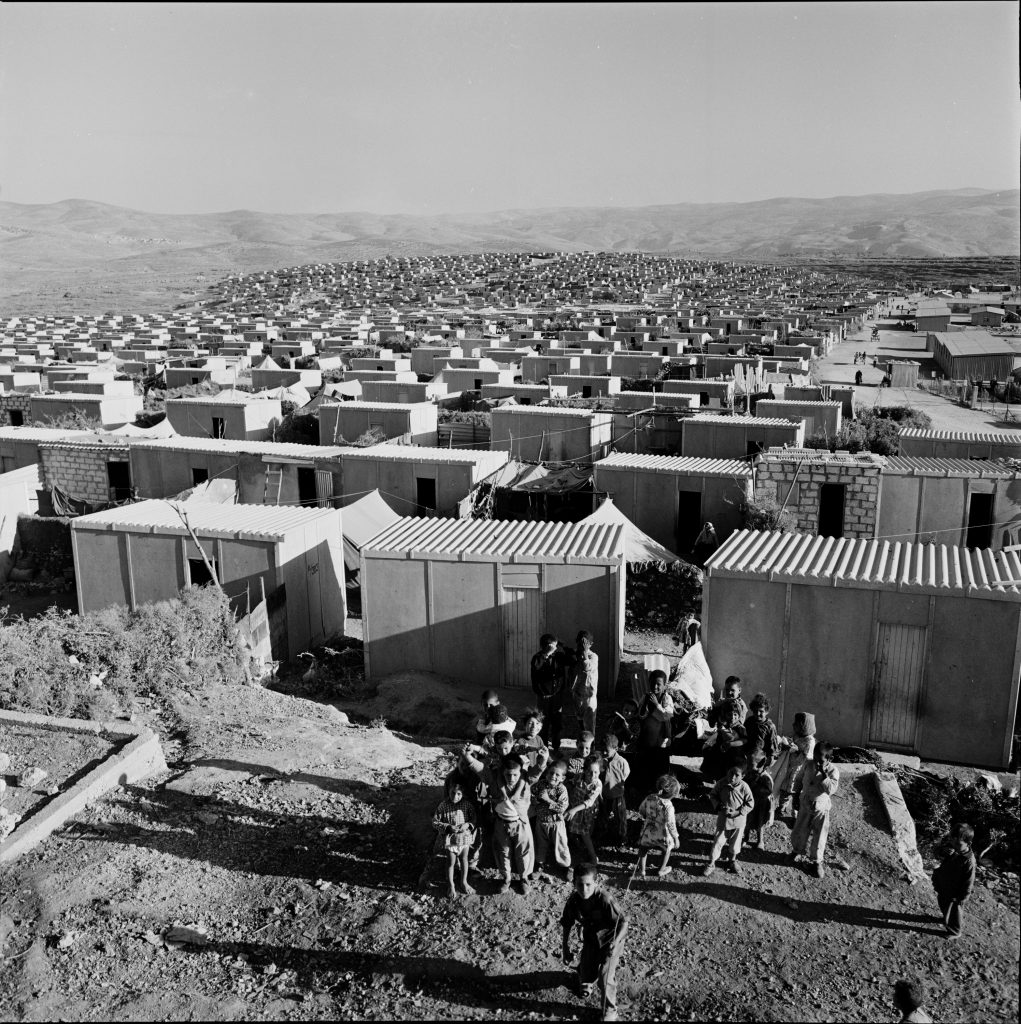

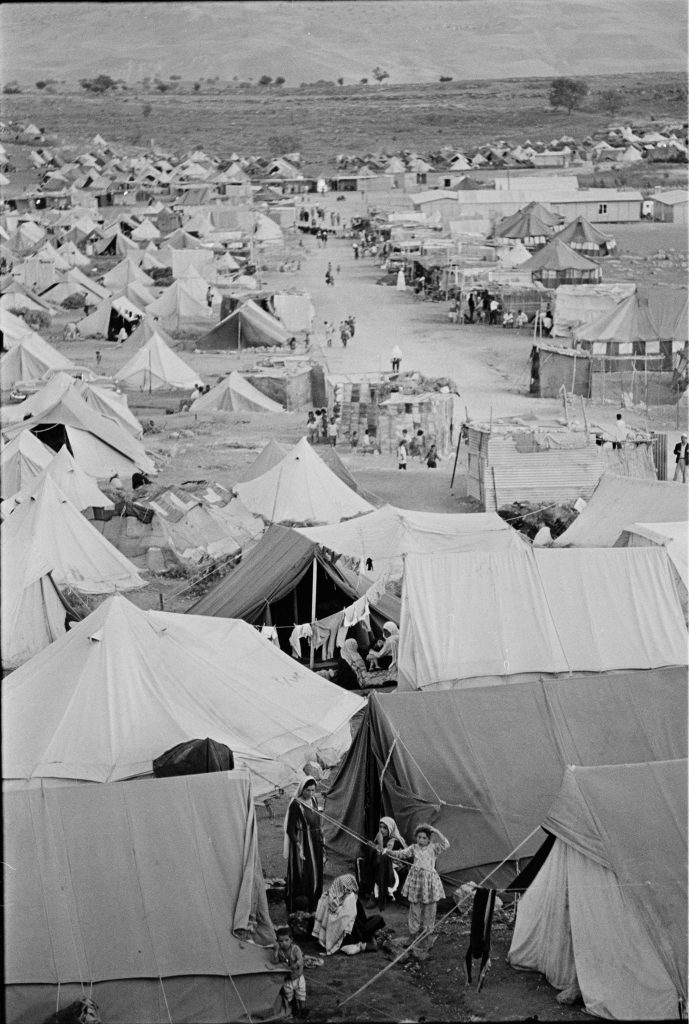

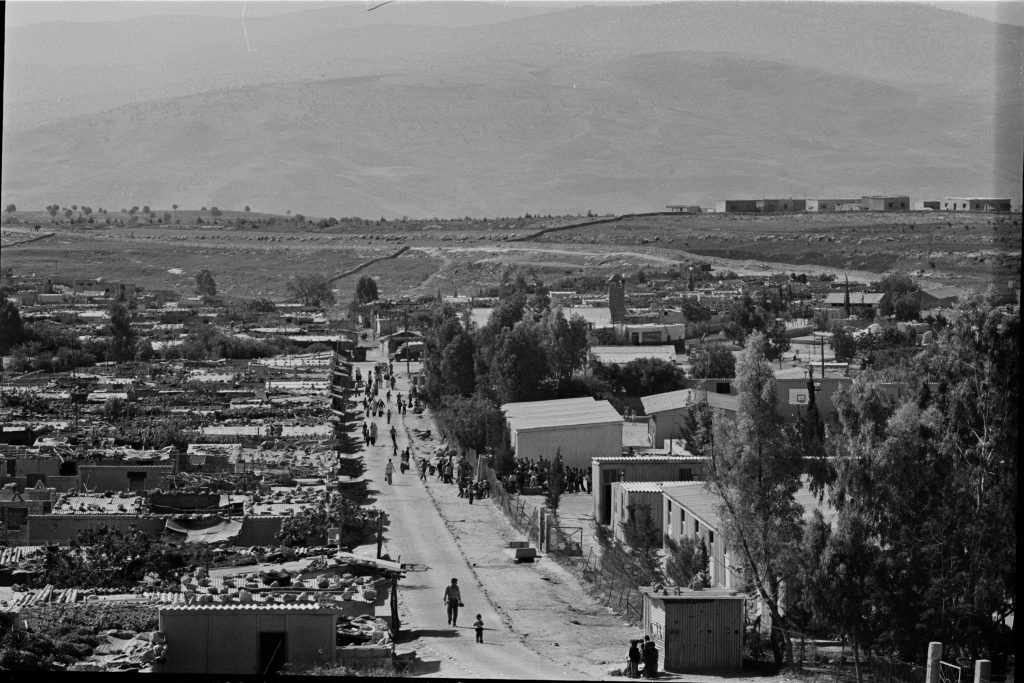

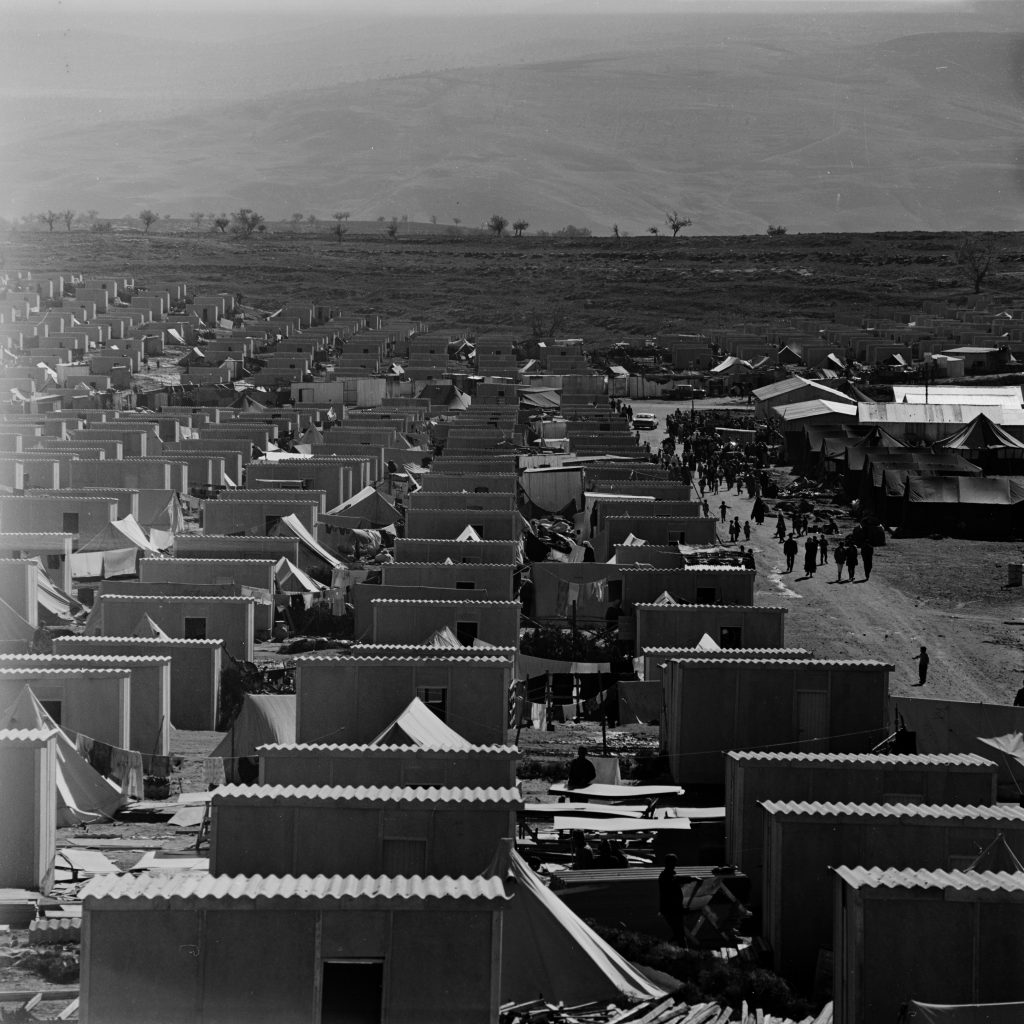

Jerash camp, known informally as Gaza camp, was set up on 0.76km2 of land in the governorate of Jerash, northern Jordan, in 1968 in an emergency measure to host about 11,500 Palestinian refugees who had come from Gaza.

Between 1968 and 1971, emergency donations managed by UNRWA were used to build 2,000 shelters. As time passed, many Palestinian refugees replaced their makeshift housing structures with more durable concrete homes, yet many roofs are still made of corrugated iron and sheets of asbestos, exposure to which has serious health risks.

Current UNRWA statistics set the number of registered refugees in Jerash camp at 29,000. The vast majority are Palestinians who fled Gaza for Jordan after the 1967 war having previously been forcibly displaced from their homes in what became Israel or their descendants. Israel bars them going to live in either Israel or Gaza.

Only 6% of them are Jordanian citizens. Some 90% hold two-year temporary travel documents. They depend on the food coupons and packages and health and education services provided by UNRWA.

According to a study published in 2013, UNRWA considered Jerash camp to be the poorest of the 10 Palestinian refugee camps in Jordan, with 52.7% of its residents having an income below the national poverty line.

UNRWA is the only source of primary health care for the Palestinian refugees in the camp. This includes medical care for chronic diseases such as diabetes and hypertension (high blood pressure). It also covers part of the hospitalization fees in public hospitals for camp residents without Jordanian citizenship.

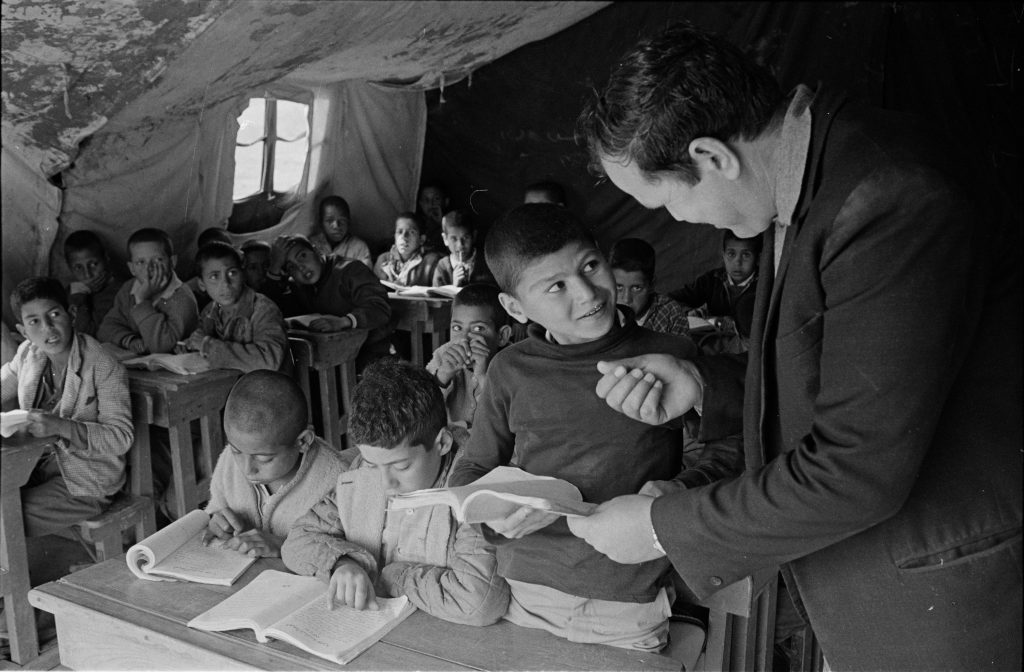

UNRWA is also the sole provider of education for children in Jerash camp. Four UN schools in two buildings work in double shifts. Classrooms are overcrowded and lack adequate facilities. Only 13% of the children in the camp pursue higher education.

Palestinian refugees in Jerash camp have very restricted access to employment given that, in the vast majority of cases, they are not Jordanian citizens. The camp is also in a rather remote area with limited access to employment opportunities.