Chapter 1: The Occupied Palestinian Territories

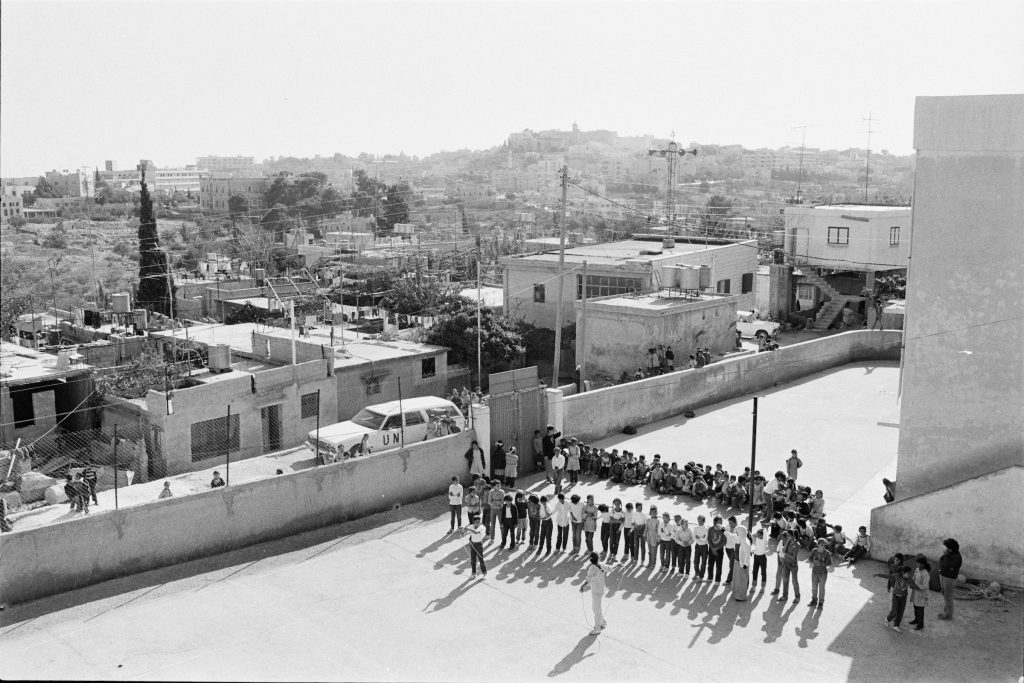

Aida Refugee Camp

The Gaza Strip

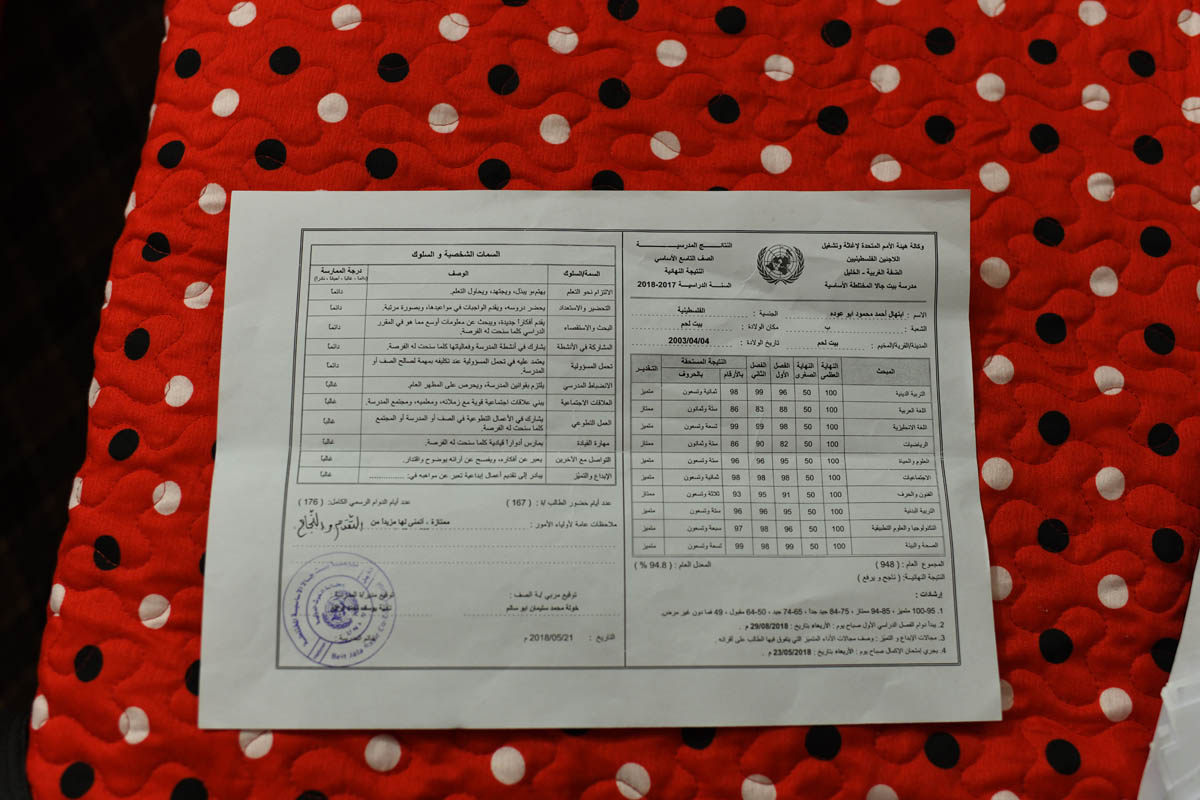

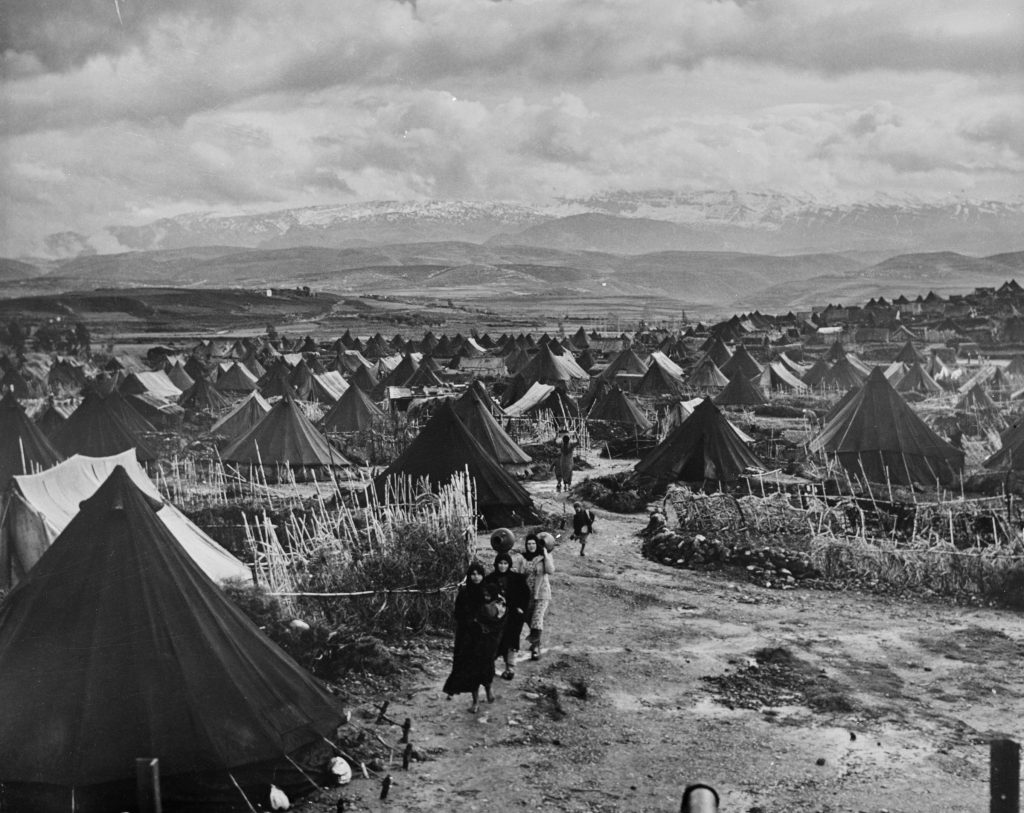

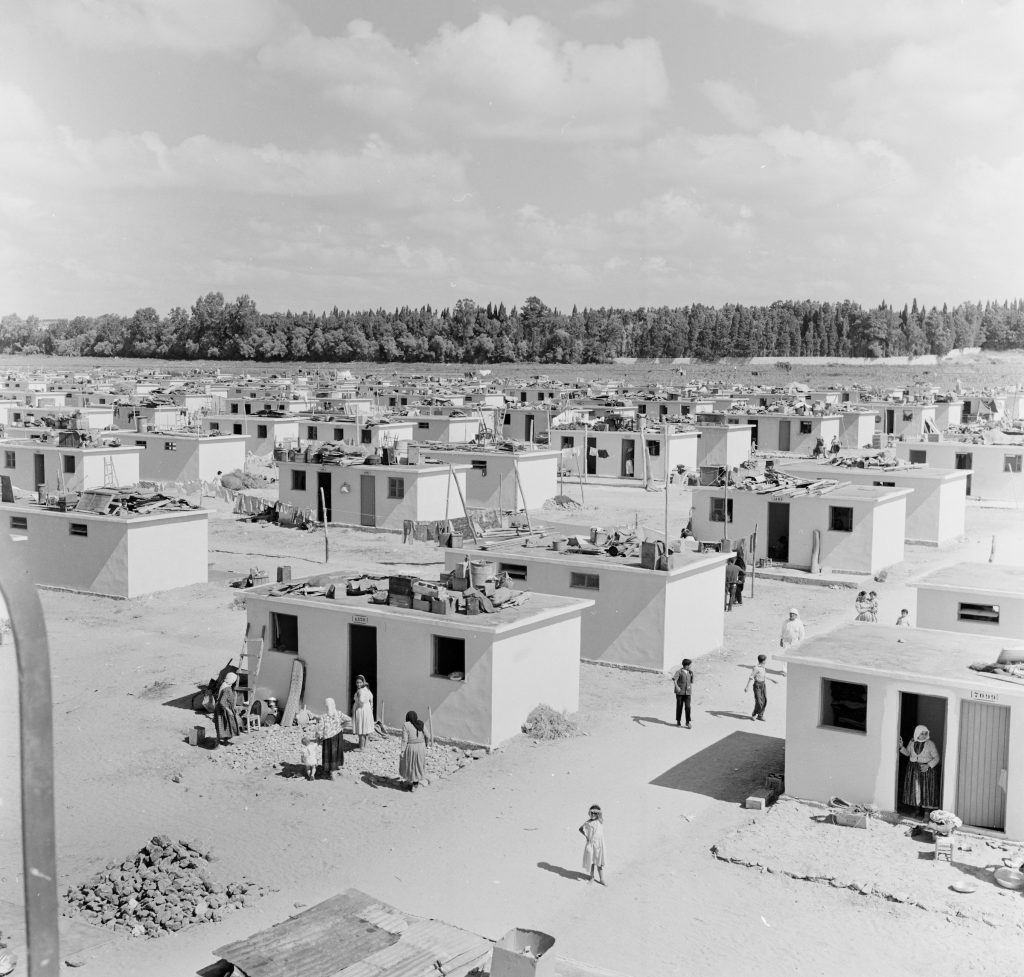

More than 2 million Palestinians living in the Occupied Palestinian Territories are registered as refugees with the UN Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA); around 775,000 live in the West Bank, while 1.26 million reside in the Gaza Strip. Many live merely a few kilometres away from their families’ original homes inside what is now Israel, yet they continue to be barred their right to return there. Aida camp is located in the West Bank, 2km north of Bethlehem, and is home to approximately 3,300 Palestinian refugees. They live in an area that covers only 0.071km2, or the size of around 10 football pitches. The elder generations can still remember their original homes in the villages around Jerusalem that they had to leave in 1948, during the war that created the State of Israel. Their home today is surrounded on three sides by an 8m-high concrete wall, punctuated by five Israeli military watchtowers. The main checkpoint between Bethlehem and Jerusalem, which is operated by Israeli forces, sits nearby. The Israeli settlements of Har Homa and Gilo, illegal under international law, are visible from the rooftops in the camp.

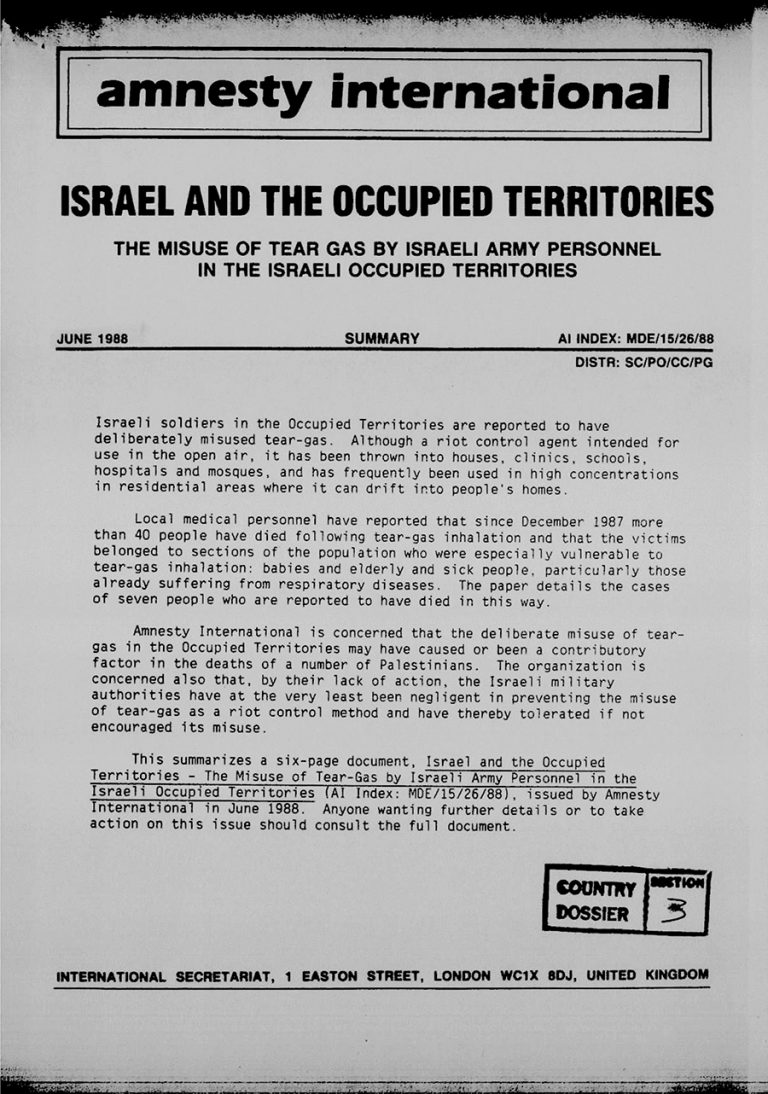

Israeli restrictions on movement prevent most camp residents from crossing the checkpoint to go and find work, and the wall makes it impossible for them to extend their homes. The buildings in the camp are becoming ever more crowded, and run down. The nearby checkpoint is often a site of protests and confrontations between the Israeli army and Palestinian youths from the camp. As a result, the camp’s residents face frequent raids by Israeli forces, who use unnecessary or excessive force, including reckless use of tear gas and rubber-coated bullets, when dispersing the protests. Abd al-Rahman Obeidallah, aged 13, was shot by an Israeli soldier on 5 October 2015 as he was standing about 70m from clashes between Israeli forces and Palestinian youths, while posing no threat. He died in hospital shortly afterwards; doctors said he was killed by a gunshot wound to the chest. In one year alone, between June 2017 and May 2018, the Israeli army carried out 105 military operations inside the camp – an average of around two operations a week. During the same period, people inside the camp recorded 43 occasions in which Israeli forces used tear gas. In some cases, the Israeli army fired tear gas indiscriminately into the camp from behind the concrete wall. In others, soldiers fired directly at people’s homes and other buildings, including mosques and schools. Residents say that the soldiers do not issue warnings and that they are liable to fire tear gas canisters at “any moment”. The firing has become so frequent that residents have covered the camp’s football pitch with mesh netting to stop tear gas canisters from entering.m According to residents, in the weeks that followed US President Donald Trump’s recognition of Jerusalem as the capital of Israel on 6 December 2017, Israeli soldiers fired tear gas at the camp almost daily, causing huge anxiety among the residents and disturbing their work, studies and other activities. In a recent study, the Human Rights Center at the University of California has found that the Israeli forces use tear gas in Aida camp frequently, indiscriminately and in a widespread manner. 100% of the 236 residents surveyed in the study reported being exposed to tear gas in 2017, with some reporting being exposed to tear gas two to three times per week for more than a year. Many said that they were exposed to tear gas in their homes, at work or school while posing no threat. They reported loss of consciousness, breathing difficulties, rashes and severe pain as a result. The study also found that many residents suffer from distress consistent with high levels of anxiety and depression, including sleep disruption and chronic post-traumatic stress disorder. Perhaps most disturbingly, residents expressed high levels of fear of the possible long-term effects of the exposure to chemical irritants; they associated chronic conditions such as asthma or miscarriages with the exposure to tear gas, though evidence to back up such claims is difficult to obtain as there is no long-term research on the health effects of tear gas. However, according to medical experts, the confined area, the overcrowding and the prolonged exposure to very high levels of toxicity increases health risks for those affected, especially children, pregnant women – particularly those with a predisposition to miscarriages – and people suffering from chronic diseases. The use of tear gas is only permissible for the purpose of crowd dispersal; it should not be used in confined areas. People must be warned that tear gas will be used and they must be allowed to disperse. Israel’s use of tear gas in Aida camp is abusive and contrary to international human rights standards on the use of force by law enforcement officials.

As many as 70% of the Gaza Strip’s population of 2 million are registered Palestinian refugees from areas that now constitute Israel. Over the last 12 years, they have suffered the devastating consequences of Israel’s illegal air, sea and land blockade, in addition to three wars that have taken a heavy toll on essential infrastructure and further debilitated Gaza’s health system and economy. As a result, Gaza’s economy has sharply declined, leaving its population almost entirely dependent on international aid. Gaza now has one of the highest unemployment rates in the world, estimated at 44%. Four years since the 2014 conflict, some 22,000 people remain internally displaced, and thousands suffer from significant health problems that require urgent medical treatment outside of the Gaza Strip. However, Israel often denies or delays permits to those seeking vital medical care outside Gaza, while hospitals inside the Strip lack adequate resources and face chronic shortages of fuel, electricity and medical supplies caused mainly by Israel’s illegal blockade. The situation in the Gaza Strip has become so untenable that in 2015 the UN warned it would become “uninhabitable” by 2020. As the occupying force, Israel controls all access to Gaza, with the exception of the Rafah crossing on the border with Egypt. Israel continues to control the Palestinian population registry, so all identity documents, including passports, require Israeli approval. As a result, the movement of people and goods is severely restricted and the majority of exports and imports of raw materials have been banned. Travel through Erez, Gaza’s passenger crossing to Israel, the West Bank and the outside world, is mainly limited to what the Israeli military calls “exceptional humanitarian cases”, meaning those with significant health issues, and their companions. Meanwhile, Egypt has imposed tight restrictions on the Rafah crossing since 2013, keeping it closed most of this time. The UN and the International Committee of the Red Cross, among others, have declared Israel’s closure policy “collective punishment” and called for Israel to lift its closure.

Against this backdrop, on 30 March 2018, Palestinians in Gaza, including refugees, launched the Great March of Return, a series of mass demonstrations along the Israel-Gaza fence to demand their right to return to their villages and towns in what is now Israel, and to press for an end to Israel’s blockade. Israeli soldiers and snipers responded with live ammunition and tear gas, killing over 180 Palestinians, including at least 32 children, and injuring thousands of others, some with what appear to be deliberately inflicted life-changing injuries. In many of the fatal cases recorded by Amnesty International since the protests began on 30 March, victims were shot with live bullets in the upper body, some from behind. Eyewitness testimonies, video and photographic evidence suggest that many were deliberately killed while posing no immediate threat to the soldiers who killed them. Two journalists and three paramedics are amongst those killed; many others were injured. According to the findings of a report published by the United Nations Commission of Inquiry, between 30 March and 31 December 2018, over 6,000 people were injured with live bullets, while thousands suffered from tear gas inhalation. Many reported fainting, dizziness and headaches, in some cases even days after inhaling the tear gas. The protests culminated on 14 May, on the day of the US embassy’s move to Jerusalem and the eve of the 70th anniversary of the Nakba. On that day alone, Israeli forces killed 59 Palestinians, in a horrifying example of the use of excessive force and live ammunition against protesters who were not posing an imminent threat to Israeli soldiers located behind the fence and protected by gear, sand hills, drones and military vehicles.